If you’re any sort of film or acting buff, chances are you made up for mind about Marlon Brando a long time ago.

“Flaky” or “lazy,” a “an unrepentant womanizer” or “civil rights/Native Rights poseur,” “neglectful parent.” And that’s not even getting into the nasty acting labels — “a mumbler,” “Method Actor Run Amok,” “tantrum tosser,” “budget wrecker,” etc.

And having read several Brando biographies, including the delightful “as told to” autobiography “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” and the “Listen to Me, Marlon” documentary, I typically pick up any new one that comes along, turn to the index and thumb through the pages about his childhood pal turned young actor running and and sometime co-star Wally Cox.

Talk about your odd couples. I always look for some fresh take on how the mismatched running mates stayed so close (until Cox’s too-early death in 1973).

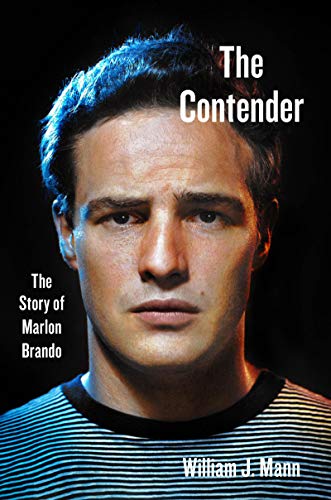

But with “The Contender,” William J. Mann (“Kate: The Woman Who was Hepburn”) tries something new. He’s going for a full-on, park the guy on a couch psychological profile, a search for what made him the wildly eccentric, bored acting genius he was — a towering talent whose imprint changed acting, but who peaked at about 30, and sleepwalked his way through a decade or more until his “Godfather” comeback.

Feel free to raise an eyebrow, as I always do when I stumble into one of these post-mortem reads of the dead and famous. Mann sets out to puncture, or at least explain and excuse every one of those “labels” the fellow carried throughout his long, storied and tabloid-stained life.

“Hagiography,” you think. As did I, here and there. There’s no excusing the way he treated women, no soft pedaling string of baby mamas, the abortions, driving Rita Moreno to attempt suicide, the ruins of lives (Brando’s two “lost” children) that frame this psycho-biography.

But Mann had access to letters, to hours and hours of tape-recording musings — some used for “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” some sampled in “Listen to Me Marlon.” Diaries of some of those who crossed paths with him are turned over, interviews with those who knew him.

The thesis Mann came up with? Brando was a victim of trauma — an alcoholic mother he had to fetch from the police station (nude, on one occasion) as a teen, the fights his parents carried on in front of him, his stern, unloving father — Marlon Brando Sr. And damned if he isn’t onto something.

He studied under Stella Adler, so calling him “Method” was the best way to piss him off. She was all about losing yourself in your “imagination.” Another way to get under his skin was to pester him with a camera. He broke one paparazzo’s jaw, and heaven knows how he would have handled the cell phone camera now.

Mann has Francis Ford Coppola recounting the “Godfather” audition clip (Never seen it, have you?) where he, experimenting with shoe polish for hair and eyebrow dye, stuffing tissues in his mouth and lowering his gaze, convinces the Brando-hating head of Paramount that he WAS Don Corleone.

The early history, with the great acting teacher Adler (his “cruel” Midwestern dad paid for acting school in New York, ahem) only taking an interest in the actor who would become her most famous pupil when an agent pressed his card on Brando after a student production, the howl of grief in “Truckline Cafe” that led to “STELLAAAAA!” in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” his indulgence and exhaustion at trying to get a version of “One-Eyed Jacks” ready for theatrical release (Paramount cut an hour out of it), all of that is handled in chapters that don’t so much go for point-by-point chronology, but for the key moments in Brando’s life.

Mann gives us the most thorough account of Brando’s civil rights activism, which started in his 20s in the 1940s, put him in Alabama demanding voting rights and equal justice in the late 1950s, and climaxed with his turning down an Oscar and giving all of America a dose of Native American struggles against racism, ill-use, an unsympathetic government and a tuned-out populace through one of the most memorable protest speeches in Oscar history.

Yes, Mann goes overboard excusing some things, always takes Brando’s side and shortchanges the last years — when the actor had a habit of taking a big paycheck, rarely trying very hard, and when he did — delightfully sending up his “Godfather” in “The Freshman” — STILL trying to sabotage the film with the press before production ended.

“Mutiny on the Bounty” probably wasn’t his fault. But he discovered Tahiti and made all his future paydays conform to his wish to buy a 1500 acre atoll there. That’s having goals, kids.

“Contender” is still an excellent read, a nice breakdown of the symbolism of the great films, and anecdotes about those who hated working with him, or idolized him (EVERYbody in the cast of “The Godfather”) and a worthy addition to the canon.

The Contender: The Story of Marlon Brando — Harper Collins, 718 pages. $35.