Italian is a lovely language for storytelling, something you can experience even if you don’t speak the language. In films, the subtitles merely pinpoint the specifics of the story being told. The rhythmic dramatic pauses and musical Italian words easily drawn out for emphasis have the hypnotizing effect of making us “know” even if we don’t quite “understand.”

It’s the perfect language for a publishing phenomenon, a writer of literary fiction who became famous late in life, who blew up in New York and America even as her native Italy was trying to decide what to do with her, how to regard her.

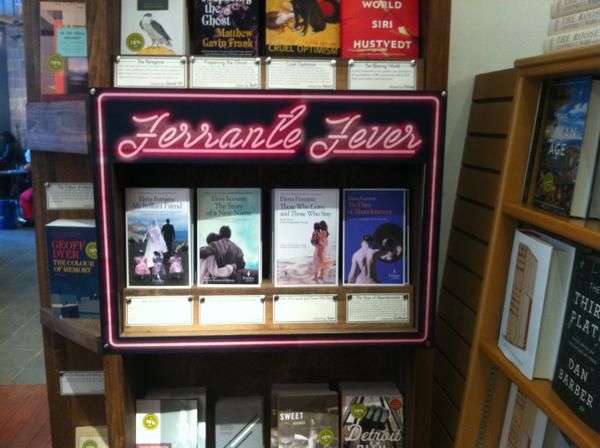

Elena Ferrante wrote “The Neapolitan Novels,” also referred to as the Neapolitan Quartet, moody, internal and seemingly somewhat autobiographical novels that became the basis for HBO’s “My Brilliant Friend.” They follow two girls, born into impoverished, violent Naples during World War II, all the way through a life of loves, mistakes and trials on into old age.

In the documentary about her, “Ferrante Fever,” Hillary Clinton confesses she’s a fan during an interview in the middle of the 2016 presidential election. Fellow novelists such as Jonathan Franzen and Elizabeth Strout sing Ferrante’s praises, and Italian colleagues, filmmakers who have adapted her and others speak of “a writer who’s telling the truth.”

Ferrante has let on that she’s unmarried, was born in Naples in the 1940s, and is a mother. Motherhood, mothers and daughters and bad mothers are recurring themes of her fiction. But Elena Ferrante is a nom de plume. We don’t know who one of the world’s most popular and “influential” (Time Magazine) novelists actually is.

“Ferrante Fever” doesn’t address that, and truthfully, doesn’t exactly break down her dozen novels in terms of plot, themes, incident or what have you.

Filmmaker Giacomo Durzi shows us animated sequences suggesting characters and states of mind.

We see clips of the Italian films (two of them) which preceded the HBO adaptation (“Fever” was filmed in 2016).

And as a woman, dressed in grey from her hat to her overcoat, walks away from the camera down city streets as we hear a narrator read (in Italian, with English subtitles) from Ferrantes’ collected letters to publishers and others, a manifesto of “The book stands alone” and other reasons she maintains her anonymity. The most convincing is her choice to eschew the pressures of having a writing career. She could just…walk away. And all she has to do is write. No writer’s conferences, festivals, publicity tours, endlessly tedious interviews.

Franzen (“Corrections,” “The Purity”) confesses to envying her that.

But with all this pussy-footing around what the books actually are about and how they read (a director mentions “like a crime novel”), the question of identity moves to the fore in “Ferrante Fever.” In avoiding the “Big Question,” and not really substituting enough of the writing, plotting and characters to give us a clear picture of her talent or make the documentary more compelling, we wonder if the fact that we don’t know who she is might be the secret to her appeal.

“Anonymous” became a celebrated writer for penning a roman a clef about the Clinton White House — “Primal Colors.” The book became a lot less interesting when we learned which overly-connected reporter on the beat wrote it.

Others have used that “mystery” as a selling point, a notoriety in itself. The novelist who wrote “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” went by B. Traven, and only was “outed” late in life — a German labor agitator and pamphleteer who escaped death threats as Hitler came to power by reinventing himself in Mexico — publishing in English (clumsy English), writing epics with big themes and working class pro-labor grit.

But suppose Elena Ferrante isn’t writing from direct personal experience, that the implied but denied autobiography isn’t what the books are built upon? There’s been research and speculation about her real identity in her native Italy.

A celebrated book of the ’70s and ’80s was “The Education of Little Tree,” an “authentic” portrait of growing up poor and Cherokee in Depression Era Appalachia. It turned out to have been written by a white supremacist and KKK member.

How will the National Book Award endorser, the English language translator (Anna Goldstein) and others who speak of how “empowering” these damaged, unrepentant women characters are feel about the books if it turns out, as has been speculated, that a man did the writing?

The anonymity is a big deal, even if the folks quoted here don’t want to admit it.

Lisa Lucas of the National Book Foundation (which hands out the National Book Awards) attributes the writer’s success to not just reviews, but the original viral” path to literary fame — passing a book around among your friends.

Goldstein, her translator, says Ferrante “shows you what you might not want to know about yourself.”

Franzen tore through the quartet in 15 days while on a book tour of his own and labels her “a writer who’s telling the truth.”

And a fellow Italian novelist smiles at the reluctance of Italy to give Ferrante “her” due with a bit of schadenfreude — “Success is never easy to forgive.”

But as we pass “peak Ferrante,” with her masterwork — “My Brilliant Friend,” “The Story of a New Name,” “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay” and “The Story of the Lost Child” — adapted into eight HBO episodes, we ask the hard question that “Ferrante Fever” never asks.

After the hype, the publishing phenomenon, the embrace by the academy, is there a legacy, a permanent place in the literary firmament?

Or is this just this generation’s great publishing stunt or worse, works of merit inflated in value because of the back-story fans and taste-makers have invented, even if only in their minds, a personal history that could turn out to be a myth?

MPAA Rating: unrated, profanity

Cast: Elena Ferrante, whoever she or he might be, Jonathan Franzen, Anna Goldstein, Michael Reynolds, Elizabeth Strout

Credits: Directed by Giacomo Durzi, script by Laura Buffoni, Giacomo Durzi. An RAI Cinema/Greenwich Entertainment release.

Running time: 1:11