There are advantages of access and deep knowledge of back-story in having an adoring nephew make a documentary about your life and work.

And there are equally obvious disadvantages — over-familiarity that leads to crucial omissions of how one came to be what one became, temerity in approaching touchy family subjects.

Both are amply on display in actor-turned-director Griffin Dunne’s glossy portrait of his aunt, the celebrated essayist, journalist and novelist Joan Didion.

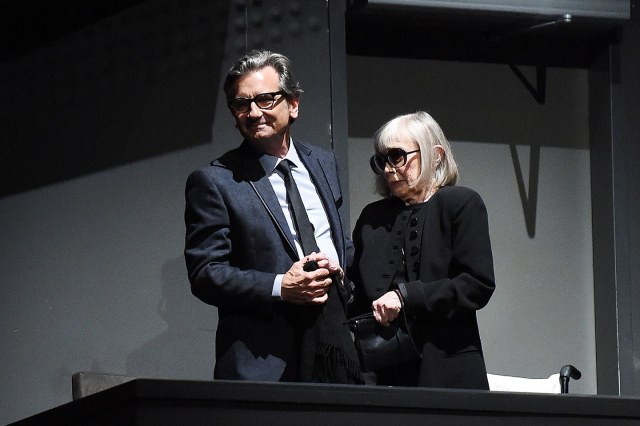

The film’s third act — focusing on Didion’s exploration of the grief brought on by the loss of her writer-husband John Gregory Dunne and adopted daughter Quintana in short order is exquisite and telling. She speaks of grief she dealt with by trying to understand and explain it in “The Year of Magical Thinking,” a best-selling memoir that became (with the help of David Hare and Vanessa Redgrave) a hit play. It is touching, a revelation for anyone who has tried to understand a loss that has become all-consuming.

“Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.”

One of the film’s few insights into her technique is Didion’s credo for every perfectly-reasoned and composed essay of self-study.

“If I examine something,” the 82 year-old Didion explains, “it’s less scary.”

But entirely too much of the preceding documentary is precious, self-absorbed, self-serving, superficial bordering on in-bleeping-sufferable.

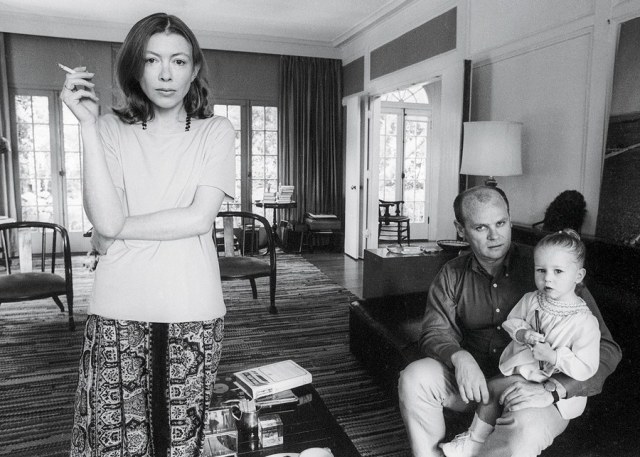

From the pointless prologue cooked-up by Dunne (“After Hours” was his most famous role), telling us of family lore that sent the Didions to “the edge of the frontier” (Sacramento, give me a break) in the 19th century, to every perfectly-composed “candid” family photograph (being friends with generations of accomplished art photographers is such a burden), Dunne depicts a clan To the Manner Born.

Didion’s husband John Gregory was younger brother od Dominick Dunne, Griffin’s dad, the Capote-impersonating true crime journalist and non-fiction best-seller. And the three of them dominated glossy magazine journalism from the ’60s through the mid-90s. In skimping so much in the details of how this dynasty made its name, Dunne the son-nephew makes it like his forebears did it with the effortlessness of gods.

There’s too little about process — beyond Didion’s omnipresent need for cigarettes, sunglasses and Coca-Cola. She started her career at the top (“Vogue”) thanks to winning a contest the magazine mounted in the 1940s in search of new writing talent.

And once she got there, she married into a family of equally promising talents. The three of them, as they immersed themselves in New York’s literary/journalistic/fashion/power scene, and that of Los Angeles, sustained each other with gossip. And parties — lots of parties where the cutting edge of this scene or that one (Janis Joplin, et al) mingled with hip writers.

For Didion, that led to acrid essays and articles on everything from 1960s Haight Ashbury to the dirty war in El Salvador, delivering pointed portraits of hippies, Hollywood shakers and movers (leading to screen producing and screenwriting credits for her and her writing partner/husband) and infamously, Dick Cheney.

The film delivers appreciations and recollections from peers such as Calvin Trillin and Anna Wintour, to a funny remembrance from a then-young actor who took leave of a faltering big-screen career to do Hollywood carpentry and Malibu beach house renovations — Harrison Ford.

Peppered through it all is the writing, pithy and spare and exacting. And when need be, capturing the moral bankruptcy of a hippy generation that let her see a five year-old they’d dosed with acid, or the crimes of Reagan policy, Bush/Halliburton corruption and ineptitude, she could be scathing in a way that permanently wounds.

On Dick Cheney — “He reached public life with every reason to believe that he would continue to both court failure and overcome it, take the lemons he seemed determined to pick for himself and make the lemonade, then spill it, let someone else clean up.”

“I like to sit around and watch people do what they do,” she explains. “I don’t like to ask questions.”

Griffin Dunne asks her a few questions, more to do with family memories (which he co-stars in, often) than anything that adds to our understanding of Didion. The most potent interview in the film, which includes many snippets of Didion chats over the decades, was conducted by Tom Brokaw during the 1970s when he was with “The Today Show.”

Dunne the younger seems intent on trying to mimic Aunt Joan’s “sit around and watch.” And all he really lets us see are the wildly florid hand-gestures Didion uses when conversation fails her, the dark glasses and the remote mystique of this canny observer of the “rising paranoia” of the American scene. The how and the why, to a large degree, remain a mystery behind those damned dark sunglasses.

Rating: unrated, with profanity, adult themes, drug usage discussed

Cast: Joan Didion, Griffin Dunne, Harrison Ford, Hilton Als, Tom Brokaw, Amy Robinson, David Hare

Credits:Directed by Griffin Dunne. A Netflix release.

Running time: 1:34