If you’ve ever bought a pass to an entire film festival just to see the restored Fritz Lang masterpiece “Metropolis” or Abel Gance’s “Napoleon,” ever driven across state lines just to catch the post-restoration re-release of “Lawrence of Arabia,” or signed up to a streaming service to ensure you wouldn’t miss the stunningly-preserved 1964 documentary epic “Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba),” you are the target audience for “Film, the Living Record of Our Memory.”

This broad and sometimes overwhelmingly thorough celebration of the unsung preservationists archiving and restoring the film heritage of countries, continents and the human race should be on any film buff’s radar.

Inés Toharia Terán has made a documentary that dares to mimic the “overwhelmed” experience every archivist, from the Museum of Modern Art, George Eastman Museum and the Library of Congress, to the British Film Institute, Cinematique Francais, across Europe and Asia, Africa and South America faces every day.

There’s just so much to take in, so much to hunt down, so many films that’ve already been lost, so much to preserve and present to film lovers, historians, anthropologists and everybody else. Where do you start?

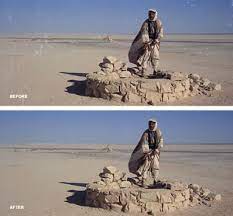

Terán takes us into labs and revisits film history through restored archival footage. A legion of preservations, historians, advocates and famous filmmakers such as Wim Wenders, Fernando Trueba and Costa-Gavras take us through the myriad of problems facing these under-funded and over-worked history detectives. They’re battling to preserve our film heritage, rewriting history as we learn all that earlier generations of historians missed due to what’s been lost. And we see what’s worth saving to that end, not just pop hits but moving images preserving whole populations, eras, cultural trends, famous personages and the forgotten masses.

Nitrate films made before 1950 are mostly lost, some “80-90% of silent films” gone forever, early works by Hitchcock and Melies, Alice Guy are gone, with only slim odds of some new treasure trove turning up and filling in film history.

Early and even established studios recycled silver-coated early film stock for its metal value, Universal, most notoriously. The huge fireproof vaults where studios stored prints and negatives were prone to fires, thanks to the explosion chemistry of early film stock.

With every lost film, there’s more lost history. And what’s been found and restored, generously sampled in “The Living Record of Our Memory,” opens our eyes — home movies of harvests during The Great Depression, the aftermath of vandalism of Jewish businesses in 1930s Vienna, late era Dutch colonialism in Indonesia, to say nothing of the pre-fame appearances of later-famous actors and directors.

“Living Record” celebrates the triumphs of detective work, painstaking restoration and presenting lost history to the masses, often via Youtube, which as more than one archivist notes, “isn’t an archive,” but is great for getting these often entertaining “artifacts” back in front of eyeballs.

Think “the talkies” began with “The Jazz Singer?” Oh no. The cinema’s first great pioneer, Thomas Edison, may not have been able to get his 1913 soundtrack and film image to sync up in all the nickelodeons that showed “Nursery Favorites,” despite experimenting with talking movies since 1894. But preservationists, with the footage and the soundtrack in hand, fixed that and put it on Youtube.

At several points during this eye-opening film, the parameters expand and expectations are upended. The first archivists were collectors who began storing motion picture prints on the scads of different formats, from the countries where the cinema was born — the U.S., France, and Britain — before the end of the 19th century. They set the tone for archivists/completists to follow, private collectors to university and national archives.

More recent preservationists have broadened what must be included in the world’s cinematic heritage, from pre-movie camera magic lantern show materials and dawn of cinema footage to classics, 120 years of Olympic Games footage to home movies, “lost” works by famous film artist, the Hollywood-sized industrial film/educational film industries’ product to even Youtube and TikTok ephemera of today.

Albert Einstein never learned to drive. But as a lark, a studio put him and his wife in one for a little special effects featurette that captures the great thinker at his most whimsical.

The “never knew that existed” visuals are accompanied by a bit of myth-busting. No, “digital archiving” is not the answer to this ongoing problem of deteriorating film stock and lost titles. Digital storage media — none of them — last a fraction as long as celluloid negatives and prints kept in cool, dry, cared-for archives.

The “cloud” isn’t the answer, and gigantic power-sucking servers aren’t either. The pie-in-the-sky possibilities suggested here suggest that the process of “migrating” preserved digital copies of historically significant material will be ongoing as the tech evolves in ever faster cycles.

One of the best arguments for doing this points to the ways previous revivals of interest in various corners of film history have sparked explosions of creativity amongst new generations of filmmakers.

The French New Wave, the L.A. Rebellion, the VHS video revival, the collectible disc mania, streaming, the rise of documentaries shot on cell phones, each has been inspired by renewed interest in the medium’s history, widening who gets to make movies and thus broadened the cinema’s reach.

There’s simply too much in this documentary to summarize without leaving out scores of other access points to film fans, cultural historians, filmmakers and students of the cinema. The one gripe with “Record of Living Memory” is that it’s too broad and tries too hard to cover too many bases.

But if you were an archivist or a film loving film editor, what would you leave out?

“Film, the Living Record of Memory” played a lot of film festivals, and now it’s showing up in cinemas as it moves to streaming. If you love movies and think you know the medium’s history, prepare to be overwhelmed.

Rating: unrated

Cast: Wim Wenders, Costa-Gavras, Ridley Scott, Celine Ruivo, Bryony Dixon, Grover Crisp, Benjamin Chowkwan Ado, Lotte Eisner, Ann Adachi-Tasch, Vittorio Storaro, Te-Ling Chen, Margaret Bodde, Kevin Brownlow and many others

Credits: Scripted and directed by Inés Toharia Terán A Kino Lorber release.

Running time: 1:58