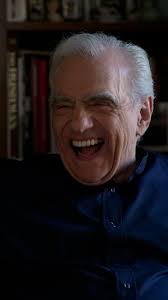

Film buffs idolize him. Film students long to become him. His fellow filmmakers emulate him. Actors long to work with him. And film journalists relish the chance to bask in his presence and find something to ask or say to him that gets that infectious laugh going.

Martin Scorsese emerged as America’s most important movie maker with “Raging Bull.” Hollywood took a bit longer to figure that out. But his decades without Academy Award recognition just burnished his myth, the “maverick,” the artist, the “Hollywood outsider” who made the Greatest American movies in spite of “the system,” “the club” he was never wholly welcomed into.

“Mr. Scorsese” is a deep and somewhat intimate dive into the totality of one of the cinema’s greatest artists, the sort of epic treatment of the director of “Goodfellas,” “Taxi Driver,” “The Wolf of Wall Street” and “The Last Temptation of Christ” that Scorsese himself gave one of his idols — Bob Dylan — for PBS.

Actress turned director (“Personal Velocity,” “”Maggie’s Plan”) and “Mr. Scorsese” director and interviewer Rebecca Miller is part of the extended Scorsese film family. The daughter of the great playwright Arthur Miller is married to Daniel Day-Lewis, who starred in a couple of Scorsese classics — “Gangs of New York” and “The Age of Innocence.”

That gave her access to most everybody who was or is anybody in Scorsese’s life story — from his most famous collaborators DeNiro, DiCaprio and Pesci to his legendary editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, “Taxi Driver” screenwriter turned director Paul Schrader to his most famous ex-wife, Isabella Rossellini.

But her real coup might have been rounding up Scorsese’s paisonos — not just his fellow Italian Americans in the movies — director Brian DePalma, Robert DeNiro, writer Nicholas Pileggi, Leonardo DiCaprio — but his running mates from childhood.

The “small” and “asthmatic” Scorsese grew up with a rough and tumble crew in Flushing, Queens, and Miller interviews them and even has Scorsese sit down with them to joke around and talk about the world they came up in, with slackers, wise guys, “good” Catholics and aspiring cutthroats.

DeNiro grew up a block or two away. “Mean Streets” captured that world, and DeNiro revisited it for a Barry Levinson movie named for the local mob “social club,” “Alto Knights.”

Once Scorsese figured out the priesthood wasn’t for him and turned his passion for movies and drawing his own ersatz “storyboards” telling the stories of his favorite films into film school and then a movie making career, these figures and those settings inspired “Mean Streets” and much of the mob cinema that was to come.

“Mean Streets” truly launched his career and Miller talks Scorsese’s pals into getting the “inspiration” for DeNiro’s breakout character Johnny Boy to sit down with her and own up to the resemblence.

We learn about his earliest film education, “neorealist (Italian classics) on New York TV,” see glimpses of his early student films and learn that independent filmmaker John Cassavettes was an early mentor, one who kindly chewed him out for taking on a cheap Roger Corman-produced genre picture (“Boxcar Bertha”) and planning on another (“I Escaped from Devil’s Island”) rather than film stories from his heart.

“Mr. Scorsese” treks through Scorsese’s life, marriages (five) and career in five episodes, capturing ups and downs, battles over “Taxi Driver,” “The Last Temptation of Christ” and the debacle that “New York, New York” became. All the periods when he could get a movie made with relative ease are contrasted with the “indulgent” and “irresponsible” rep that many of the “auteurs” of his era — Coppola and Cimino and Scorsese– earned for their sometimes cocaine-fueled (in Scorsese’s case) ego trip flops.

We see interviews and on-set chats from the era that give away Scorsese’s addiction (hyper), and his “Last Waltz” era roommate, the late musician from The Band Robbie Robertson, underscores the drug soaked milieu they were almost consumed by.

His three daughters Cathy, Dominica and Francesca talk about his failings as a father, and late life attempts to rectify that.

We hear about his volcanic temper — “Anger fuels his arts!” — and his many explorations of his religious upbringing and convictions.

We learn of the great Scorsese movie moments that were, pretty much to a one, improvisations created in collaboration between the director and DeNiro, Pesci, Day-Lewis and others, variations of the famous Matt Damon story of how Jack Nicholson expanded a murder scene into something truly sinister for “The Departed.”

DeNiro improvised his way to “You talking to me?” rehearsing “Taxi Driver.” Pesci brought “Do I AMUSE you?” to the set of “Goodfellas.”

Sharon Stone and Scorsese talk about how she cracked open the boys club and forced him to include her in that famous improv-a-better-scene process in “Casino.”

Miller finds archival clips of Godard and Bergman spying Scorsese’s genius early on, and she gets Spike Lee and Spielberg to crack up recalling this or that bit of Marty lore — from the Oscar snubs to the stories and sequences he’d consult with his famous peers on, just to get their take.

Actors and Spielberg all have a “Marty impersonation,” we quickly figure out.

Schoonmaker is one of the anchor interviews here and she and Pileggi talk about the director’s musical tastes and ways of plotting, story-boarding, shooting and editing scenes set to classic pop, blues and Rolling Stones rock.

The five part film has some notable omissions. Francis Ford Coppola isn’t interviewed, and he’s the director who talked Ellen Burstyn into pursuing the young Scorsese for “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.” The only ex-wife or ex-girlfriend interviewed are people in “the business,” and not every film is mentioned must less explored.

The contrary voices here come from decades of film reviewers — newspaper and magazine headlines, Siskel and Ebert. But Scorsese comes off as far and away his own harshest critic.

He comes off here the way he does on talk shows and in any interview — thoughtful, taking questions and his answers seriously, laughing easily. I interviewed him when “Gangs of New York” came out, can confirm how “disturbed” he got making “Shelter Island” and later had a lot of laughs with him over his obsession with The Rolling Stones when he got to shoot a concert film with them some years back.

His last couple of films have their cheerleaders, and critics (like me) who think “The Irishman” and “Killers of the Flower Moon” were lesser Scorsese. But he’s forgotten more about film and film making and film history than any ten people you could name put together. He’s made film restoration a late life passion, and if you enjoy the cinema of Michael Powell, you can thank Scorsese for saving his work.

“Mr. Scorsese” is better than any written biography of the filmmaker could ever hope to be, a thorough, soul-and-psyche-searching exploration of an artist and why he makes the art he films. Best of all, it invites the viewer to go back and re-watch the hits, the flops, the greatest concert film of them all (“The Last Waltz”) to the dream project/exploration of faith and humanity that was widely condemned by religious nitwits who never bothered to watch it (“The Last Temptation of Christ”).

Scorsese and Spielberg were the great exemplars of the “film school generation” of “New Hollywood” directors. As “name” directors all but vanish from business model (Ari Aster is the youngest filmmaker interviewed here), “Mr. Scorsese” stands as a five part monument to the auteur theory of filmmakers, and why in his case, it’s the only explanation for his art that we need.

Rating: TV-MA, profanity, violence, nudity

Cast: Martin Scorsese, Thelma Schoonmaker, Steven Spielberg, Robert DeNiro, Jodie Foster, Cathy Scorsese, Brian DePalma, Paul Schrader, Leonardo DiCaprio, Domenica Cameron-Scorsese, Isabella Rossellini, Sharon Stone, Nicolas Pileggi, Daniel Day-Lewis and Spike Lee.

Credits: Directed by Rebecca Miller. An Apple TV+ release.

Running time: Five episodes @:52-56 minutes each