With its long pre-production process and almost as long release schedule, cinema has never been the most deft medium at surfing the tides of pop culture. Trends bubble up or explode, and like a time-delayed bomb, movies get hold of it, often after it has crested.

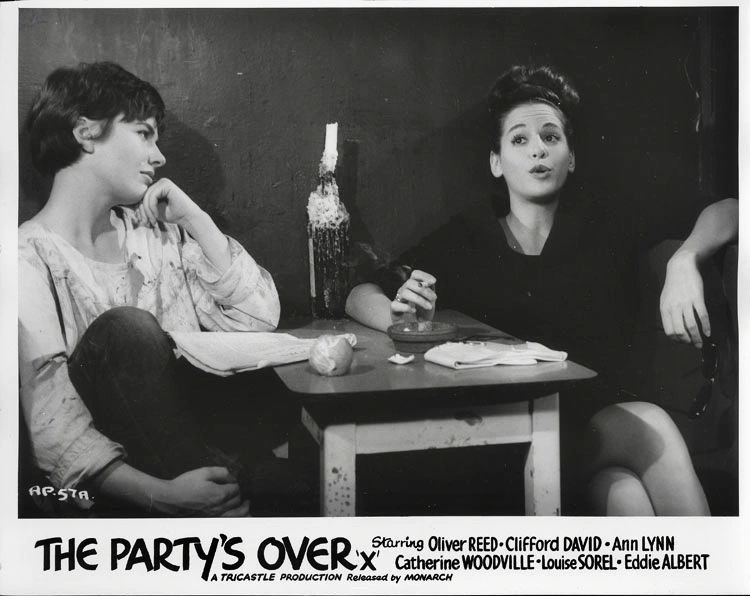

The British drama “The Party’s Over” plays like a World War II generation (adults) take on the self-absorption and nihilism of a post-war generation that was already moving beyond the poetry, art, cool jazz and “getting high” obsessions of The Beatniks and paddling out to catch the Mod wave that heralded London’s Swinging ’60s.

Here’s a curiosity of a film that plays a little square, a tad raw, and cautionary without quite curdling into “Reefer Madness” camp.

As our voice-over narrator tries to assure us under the opening credits, “The Party’s Over” isn’t “an attack on Beatniks.” It’s merely a reminder that growing up will teach you that sometimes “kicks aren’t enough.”

A pre-stardom Oliver Reed stars as Moise, centerpiece of a communal pack of hep cats who live in the same apartment building, create art or idle away the day and haunt the same clubs every night. He’s a cocksure, smirking predator who beds every woman in sight, save for “the American,” Melina (Louise Sorel), an innocent who preserved her chastity even as she grew jaded with the folkways of this wearying scene.

“I wonder, if I’ll ever have a daughter,” she ponders, drowning in resignation. “Will she get high, too? And will some hobo maul her with his thick hands?”

Melina may be ready to get out, but she’s not in the mood for rescue. That comes in the form of her fiancé “from the land of the brave and the square,” Carson (Clifford David). A young executive intent on marrying “the boss’s daughter,” he shows up, all business, and gives everybody a serious case of “Yank Go Home.”

He’s to fetch Melina, and neither she nor her new crew are having it. They prank Carson from one apartment to the next, one club or cafe or another — “She was just here…You just missed her.”

“Try Buck House, ask any cabbie and they’ll take you.”

Carson figures out the “game” with that last one. It’s slang for Buckingham Palace.

But Melina won’t be caught, won’t even be met. And over the course of a day or two, Carson figures out maybe she isn’t the one for him, that the attentions of the beguiling and more mature Nina (Katherine Woodville) are something he might want to reciprocate.

He can’t hear Melina call him “just another ghoul in my nightmare,” but he gets it.

But being a stand-up Yank from Athens, Minnesota, he’s not about to abandon his mission. Not with the boss, her Dad (“Green Acres” era Eddie Albert) on the way. That means Carson can remain our tour guide to this scene, where too many of the lads swoon over the exotic American girl they help hide, with cynical, predatory Moise as smitten as any of them.

“I’m just a dead fly in the soup of pomposity.”

With all this substance abuse (alcohol is all we see), all this live-for-the-next-“kick” impulse control, tragedy is sure to strike. That’s what “cautionary tales” are for.

The main reason “The Party’s Over” seemed instantly-dated the moment it came out is that it was filmed in 1962 and had its release delayed over some of the darker elements it portrayed.

Reed’s stardom wouldn’t arrive until “The Trap,” which came out later in 1966. Sturdy journeyman director Guy Hamilton and composer John Barry filmed this before “Goldfinger” made them both James Bond icons.

But the film that sat on the shelf for those years remains a tantilizing artifact, an older generation warning a younger one of its self-destructive tendencies with a story that features differing accounts of what goes wrong, different ways of viewing the seeming sadism or at least indifference of “the party.”

Sometimes the dancers and the jazz they’re dancing to don’t sync up, and we puzzle over the under and over-reactions of Carson to affronts and challenges that delay his “mission” and might even endanger his fiancé. His parents’ generation would have thrown a punch or two to get the Beatniks’ attention.

“Nobody here asked for American aid!”

Woodville is the embodiment of push, stylish genteel upper class slumming in the ’60s, with Ann Lynn standing out as the singer who can’t let go of the Melina-smitten Moise, even though he’s dismissed her because “She always says ‘yes.'”

Mike Pratt plays a manic artist/drummer/club-owner, “Geronimo,” and Maurice Browning is quite good as that Beat Generation “type,” the older WWII combat vet taking in how the younger crowd is testing itself far removed from fighting fascism.

But the vulpine Reed is all magnetic menace and playful accent-slinging charm, the life of “The Party” and the heart of the picture. He can see the damage he’s done and the damage others are doing, and simply will not intervene as it’s against his beliefs, or his short-term interests.

Moise and the others cannot see “The Party’s Over,” but they have to sense the end is coming. Kids even further removed from “The War” were about to upend London and world popular culture, changing the music, embracing fashion and reaching for “kicks” beyond wine and jazz and promiscuity.

“The Party’s Over,” as it turns out, is eyewitness to the moment when the new party is just getting started.

Rating: TV-14, violence, alcohol abuse, smoking, profanity

Cast: Oliver Reed, Katherine Woodville, Louise Sorel, Ann Lynn, Clifford David, Maurice Browning, Mike Pratt, Roddy Maude-Roxby and Eddie Albert.

Credits: Directed by Guy Hamilton, scripted by Marc Behm. A Tricastle Film on Tubi, Amazon, et. al.

Running time: 1:31