The golden age of big screen satire began, more or less, with 1964’s “Doctor Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” peaked with “Network” (1976) and wrapped up with “Being There” and “Life of Brian” in 1980.

Movies like “M*A*S*H,” “The Loved One,” “The Hospital”and “Nashville” made their marks in a pre-blockbuster era when studios could operate in the black (barely) with more adult fare and mostly modest budgets.

“Cold Turkey” (1971) was one of the lesser lights of that satiric era. But the film satire came out mere months before its writer, director and producer Norman Lear would unleash “All in the Family” and become perhaps the most important voice in American TV, possibly ever.

Lear’s “culture divide” TV comedies are prefigured in this broad, all-star farce. He started the work of taking on sacred cows — “the Silent Majority,” “salt of the Earth” middle America and its generally contradictory values, hypocritical mores and often deranged politics — in “Cold Turkey.”

He sent up American “get mine” greed, science skepticism, a country that paid lip service to small town America while everyone living in small town America was striving to get out.

Lear’s TV work reveals him as an unabashed champion of urban America, its great cities — flawed though they were and remain.

His hook was a country that learned, conclusively, that smoking causes cancer in 1964, with warnings added to tobacco product packaging 1965, and yet the added step of banning tobacco advertising had to be taken in 1970 because damning evidence or not, we weren’t quitting fast enough.

“Cold Turkey” would be about cynical Big Tobacco’s efforts to gild its “public health/humanitarian” image by encouraging American cities and towns to quit, with a $25 million reward for any town able to do it for 30 days.

The one place to have a shot does so by having a local preacher package the message in the form of a dying town’s spiritual and economic revival. Eagle Rock, Iowa desperately needs the money. It’s emptying out, dying.

But the smokers are too addicted and too self-centered to pitch in willingly. Ultra conservatives see the mass abandonment of tobacco as “Big Government” manipulation run amok, until that is, they get to be the “enforcers” of everyone else’s behavior, conservatism’s wet dream.

As the town’s notoriety grows, our flawed, self-dealing preacher — he longs for a promotion to “Dearborn” — sees the local profiteering, the shortening of tempers and the abandonment of a common civic good and common civility. And then Big Tobacco’s operatives show up to “monitor” and if possible, cheat and tempt the town lose lose the “30 days without smoking,”” “Project Cold Turkey contest.

It stars a Who’s Who of American sitcoms to come in the ’70s, many of them produced and/or created by Norman Lear. There’s Jean Stapleton, about to become America’s ditzy mom in “All in the Family,” Barnard Hughes playing another “Doc,” Bob Newhart and his old pal/co-star Tom Poston, Paul Benedict as a hippy hypnotherapist (“The Jeffersons”), Barbara Cason and Graham Jarvis of “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” and Vincent Guardenia (“All in the Family,””Maude”).

The great radio and TV comics Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding (Bob & Ray) send up every “newsman” of the day, posting as Hugh Upson (Hugh Downs), Walter Chronic (Cronkite), David Chetley (Brinkley, and Huntley), occasionally framed in a an angelic light, the way America revered its TV anchors back then,

What sticks in the memory is how the comedy is reliant on some amusingly off-color language, the residue of Robert Altman’s sleeper hit “M*A*S*H” spilling over the rest of cinema, opening the door for “Blazing Saddles” and the like.

A string of laughs come from aged character actress Judith Lowry, playing a member of the far right Christopher Mott Society (the movie’s John Birchers), free at last to refer to this action or that idea as “It’s a bull-sh–!” I wonder if her usage was a mistake they left in the final cut?

Newhart, broadly playing the PR guru who comes up with Valiant Tobacco’s “Nobel Prize,” stands out in memories of the film for this being quite unlike most any character Newhart ever played — venal, eye-bugging, amoral and comically cruel.

Poston and Hughes play two memorable versions of the “weakest” smokers in town — Hughes, a stressed-out doctor who “never operated on anybody without a cigarette,” and Poston as the rich tippler who can’t give up smokes without giving up booze. As he even drinks while he drives, that ain’t happening.

“The booze bone is connected to the smoke bone and the smoke bone is connected to the head bone and that’s the word of the Lord!”

Dick Van Dyke and Pippa Scott play the pastor his his bored, addicted wife who at least finds relief in “the physical act of love” pushed on everyone, including her husband, as a means of coping with withdrawal.

But the culture war politics of the picture didn’t hit me in any previous viewing the way it does now. The film literally opens with a shot of the Confederate flag flying over the mansion of a Southern tobacco baron (Edward Everett Horton, in his final screen appearance).

When Big Tobacco makes a push to “police” and force its products on tiny Eagle Rock, population 4006, who do the send as enforcers? The Sons of the Confederacy, riding in a truck and trailer converted to look like a steam locomotive and rail cars.

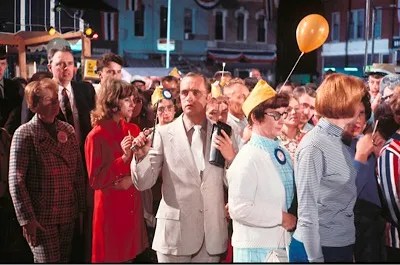

A comically chilling moment — local white Iowa kids, wearing the paper masks being sold to tourists bearing the images of the white town council, chase a lone Black child through the mobbed street scene, littered with casual Confederate Army reenactors.

Here was Lear, over 50 years ago, tying American backwardness and resistance to common sense and social progress to that font of all bad ideas — Confederate historical revanchism and the racism, conservative Protestantism and general bullheaded ignorance that goes hand in butternut glove with it.

The first musical joke in the movie is a banjo picking out the “Magnificent Seven” theme as Newhart’s “Wren” pushes the elderly tobacco patriarchy Horton around his grounds, selling him on his “biggest idea since creation,” an Alfred Nobel-inspired “change the subject from smoking-causes-cancer” contest.

That’s a reminder that this was the first film score by future Oscar-winner Randy Newman, who also sings “He Gives Us All His Love,” the ironic religious theme song to the film.

Nobody in this cast cost a fortune, and shooting it in tiny Greenfield, Iowa wasn’t the most expensive proposition. It wasn’t a complete bomb upon release, although it only made 1/8th what “M*A*S*H” earned — over $11 million — yet 30 times what Mel Brooks’ spoof-not-satire “The Producers” earned a couple of years before when it bombed on initial release.

Some of the laughs are aging better than others, but the reason to watch “Cold Turkey” today might be in recollecting its Culture Wars significance, its post-tipping point in the struggle with Big Tobacco moment in time, and in the array of talent Lear put on the screen at a bargain price.

There is literally no other movie that packaged Newhart and Poston and Van Dyke and Scott (an underrated comedienne, as evidenced here), the legendary character player Horton and the character actor actor legend in the making M. Emmett Walsh in the same movie.

And watching it anew, we don’t get to act surprised at how crackpot our politics have become, because “Cold Turkey” was stripping the “righteous rural” label right off of Middle America and folksy Iowa, way back in 1971.

Rating: PG-13 for smoking content throughout, innuendo and profanity

Cast: Dick Van Dyke, Bob Newhart, Pippa Scott, Tom Poston, Vincent Guardenia, Barnard Hughes, Barbara Cason, Judith Lowry and Edward Everett Horton.

Credits: Scripted and directed by Norman Lear. An MGM/UA release on Youtube, Amazon, Tubi etc.

Running time: 1:39