“The Passenger” is a cinematic product of a different age, when movies could be geared for a more patient audience, one willing to embrace a mystery for mystery’s sake.

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1975 Hollywood outing, a Jack Nicholson star vehicle distributed by old Hollywood itself — MGM — is sparing with dialogue and stingy with explanation. Some locations are tourist attraction obvious, many others are not named at all. It is existential in its inciting incident and obscurely vaguely vengeful in its climax, not so much defying us to understand it as demanding that we bring our own interpretation and be prepared to argue its merits.

It is, first scene to last, a “film” not a movie, “cinema” and not “content.”

Watching it now one can see it as a signpost for the end of ’60s cinema, the thought experiments of “Last Year at Marienbad,” the mind-expanding hallucination of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the indulgent excess of Antonioni’s own “Zabriskie Point,” which preceded “Passenger” and pointed towards the long wander of the end of not just his career, but of his type of art film.

It helps to have seen other films of his before tackling this exercise in impulse and emptiness for its own sake. And as the film was rescued by Nicholson’s guardianship and re-released decades later — with footage restored — on video, the fuller credits give another important clue about approaching this. Anybody who has taken a “semiotics in the cinema” course will recognize the name of one of the now-credited writers, Peter Wollen.

Semiotics, the study of signs and images and their meaning, adds weight to many seemingly vague scenes that emphasize distances, objects identified with “freedom,” the traps of life and the escape one man takes when he sees the chance.

As Antonioni & Co. take us from Saharan Africa to Germany and then through Spain, we soak up a dream “escape” that plays like a waking nightmare, a pointless trap of our hero’s own creation that he and we can only suspect holds perils beyond the simple discovery of what he has done.

We’re dropped into the Sahara with a Land Rover driver we come to learn is named David Locke. Eventually.

Locke (Nicholson) is venturing into unknown territory, making contact with locals, seeking guides and interviews. He is a conflict reporter, and this place (Chad, unnamed) has armed rebels attacking the government. The film’s long prologue shows this work — both in the fictive present and in flashbacks of interviews he’s done with officials and locals — as frustrating and dangerous. Locke ends up walking back to a town out of the desert after he gets the Land Rover good and stuck in the sand. He’s questioning the job.

“People will believe what I write. And why? Because it conforms to their expectations – and of mine, as well – which is worse.”

His confidante back at the hotel is a mysterious traveler named Robertson (Chuck Mulvehill) to whom he confesses his “detachment” and recognition of the presupositions he brings to all his interactions with Africans. And he’s married, we gather, perhaps not happily.

Finding his hotel neighbor dead in bed gets Locke to thinking. In the manner of other identity-swap thrillers — and soap operas — we see him swapping passport photos and hear “Robertson” telling the front desk a resident has died, that fellow named “Locke.”

It’s the pre-Internet, pre-commercial refrigeration Sahara of 1975. Locke must know the body won’t be preserved or shipped. Just a cause of death, notification of next of kin via the British embassy (Locke’s a Brit raised in the U.S.) and a local burial and that’ll be that.

Robertson? Locke’s about to find out just a little of who he was and what he’s about, and not quickly, either.

The modern viewer may be moved to ask questions we and the critics of the mid-70s passed over in their thrall of the Great Anonioni (“Blow-Up”) back then. Why does Locke do this? Why does he take the dead man’s appointment book and start attending meetings listed there, poking around the dead man’s house, picking up keys as if he knows exactly what they fit in, checking on lockers where something is stored that will give him clues about who he is meeting with, or avoiding?

“Il mistero della vita,” or just “Il mistero della cinema.”

It isn’t long — well, actually it is — before he has that “meeting” where an African asks him for an envoice and seems relieved Locke/Robertson has procured “the effing rifles,” if not the anti-aircraft guns he’d sought.

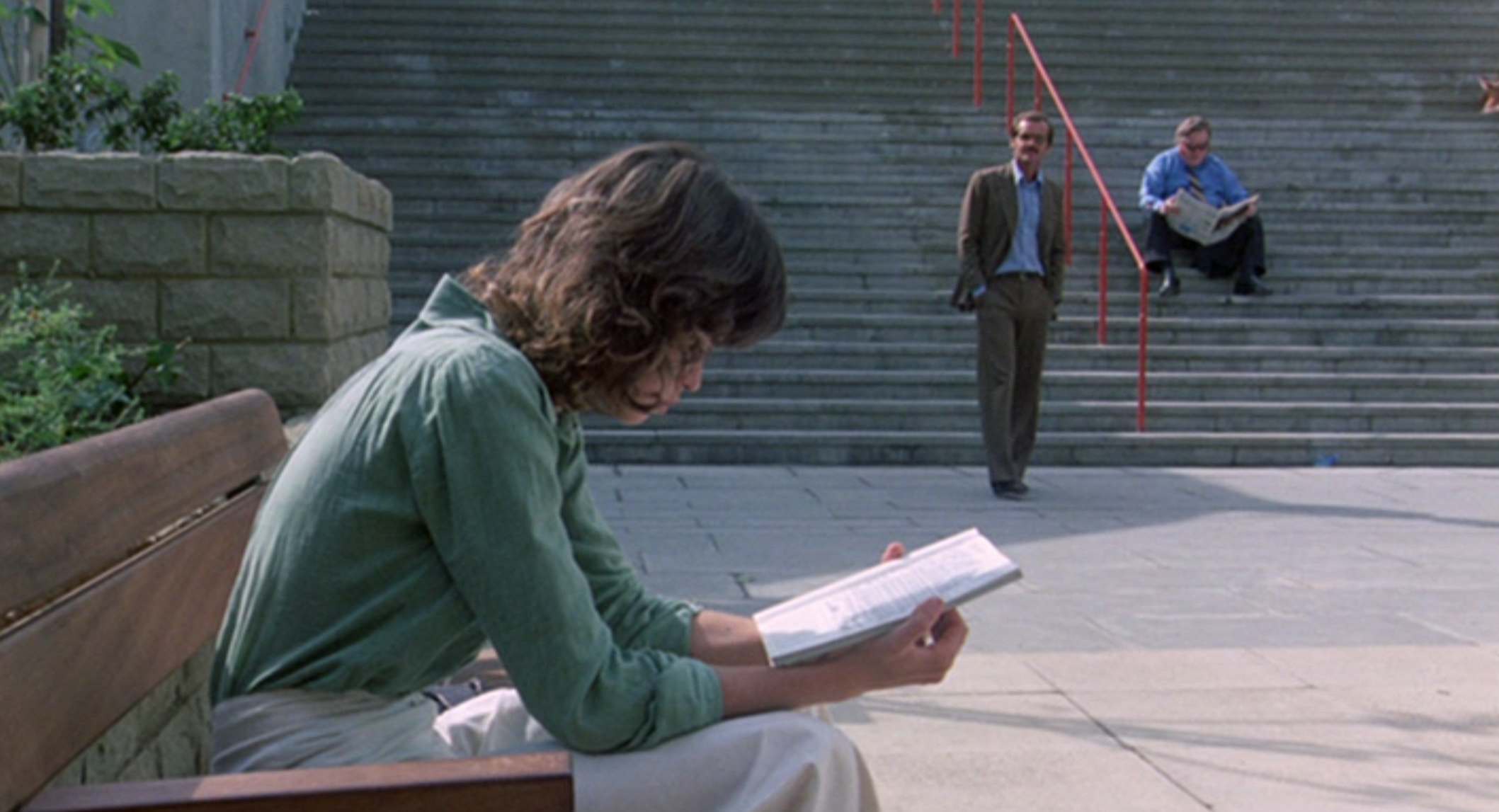

Locke seems to guess he’s in over his head. And as this isn’t just a reporter going undercover to break a story, but a man wanting a changed life, he peels off the fake mustache he’s wearing and heads, with some trepidation, to Barcelona for a meeting he may or may not take. And it’s there, among the sandcastle buildings of the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, that he notices — for the second time — this young German woman (Maria Schneider) whom he’d glimpsed in Munich.

“I used to be somebody else, but I traded him in,” he grins. Yes, he has a wife (Jenny Runacre) who thinks she’s a widow, back in the U.K. Not to worry, she’d already been cheating on her ever-absent spouse with a bloke played by veteran character actor Steven Berkoff of “A Clockwork Orange.”

“People disappear all the time,” the woman only billed as “The Girl” shrugs. She and the fellow she takes at face value soon are on the road in a late model Mercury Comet convertible he’s bought because he’s tired of telling the Avis rent-a-car clerks he’s keeping a rental “for the rest of my life.”

They dodge anybody who might be looking for him — a British TV producer (Ian Hendry) who, with his “widow,” is trying to find Robertson to ask what happened to Locke, gun runners, the Spanish police, etc.

Enthusiasts have long praised the beauty of where Antonioni puts his characters as he forces them to confront their decisions, their unraveling scheme and the emptiness of their lives. Southern Spain is displayed at its most spectacular and unspoiled (Spanish dictator Franco died shortly after the film was made). They and we take in forlorn desert roads, striking cliffside villages, friendly people and police who might give chase in their Fiat/SEATs, but have no prayer of catching an American V-8 convertible from the ’60s.

Schneider’s role is more symbolic than fleshed-in here. She’s merely a compliant female, another symbol or “sign” in the narrative about a man’s quest to escape himself.

Nicholson is free from any of the mugging that would mark his later career, just a guy making rash decisions, not spelling out what he’s doing and why because that would making things too obvious.

“The Passenger’s” Italian title — “Professione: reporter” — underscored the professional angst Locke is enduring, a journalist who has come to feel he’s part of the problem, bringing “his” viewpoint into a part of the world that is operating on its own rules and priorities. Had the film taken a more literal translation of the title, “Reporter,” we’d have pondered even longer what Locke is truly up to.

The obscurant nature of the narrative and the way it unfolds seems obvious now, removed from its time. Stealing a dead person’s identity was a trope long before this film, and endures in movies to this day.

And the celebrated six minute long-take pentultimate shot isn’t “bravura” filmmaking by modern standards, where cameras can be light and tiny and the stunt of staging, blocking and choreographing the film’s climax in a frame (with lots of off-camera sound) is closer to routine, and well within the budget and skillset of most a modern movie maker.

But “The Passenger” still pulls you in, still makes you tease out the simplest clues to get your filmwatching feet underneath you, and remains a classic study of beautiful emptiness — where to look for it, why you might crave it and just what seeking that could cost you.

Rating: PG

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Maria Scheider, Jenny Runacre, Ian Hendry, Chuck Mulvehill and Steven Berkoff

Credits: Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, scripted by Mark Peploe, Enrico Sannia, Peter Wollen and Michelangelo Antonioni. An MGM/Sony Classics release on Tubi.

Running time: 2:06

Really grateful for you bringing this movie to my and others attention. Very interesting how you used the term “content” to describe current, not cinema, but, I guess, content factory. That is what I have been calling what we are now served.

Please continue to find films like this.