I missed the HBO film “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” when it came out in 2017, even though I had read up on the story, had been tracking the film’s progress and had a personal interest in it.

HBO isn’t the easiest content provider for film critics to contend with.

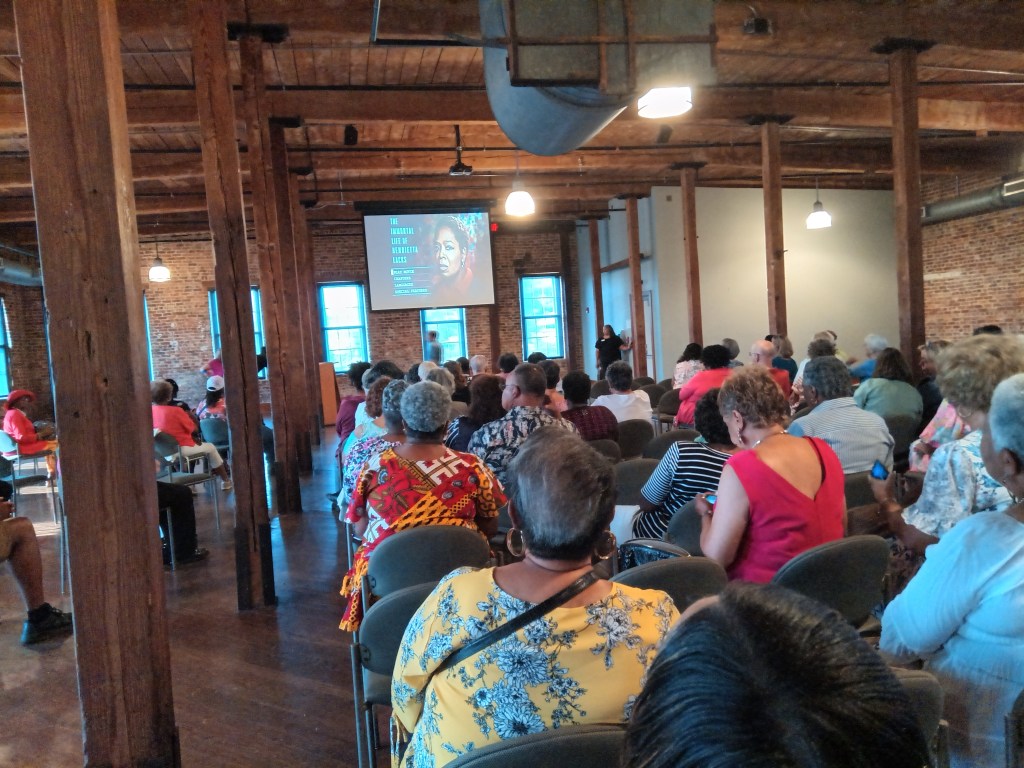

But as luck would have it, there was a showing of the movie Tuesday night, Aug. 1, in the nearest town to the village where Henrietta Lacks, who died in 1951 but whose cells made her famous, grew up.

By design, the screening in South Boston, Va., just 14 miles from Clover, Va. would be on the night of Henrietta Lacks’ 103rd birthday. And that would be the day — not coincidentally — when the Lacks family and the Thermo Fisher Scientific bio-firm that had the rights to and been selling Lacks’ “HELA” cells to researchers for generations announced a settlement of the family’s lawsuit over the exploitation of her “immortal” cell-line.

So I made the trek back to the still-largely-segregated rural town where I grew up, to a former tobacco “prizery” repurposed as a community arts center, to join a still-rare integrated event there, an NAACP-sponsored showing of a movie that did not get its due when it came out.

Beautiful, moving, and very well-acted, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” is as cinematic as any feature film HBO has ever made. It’s informative, but also poignant and pointed in its subtexts. Director George C. Wolfe, who was a playwright and celebrated stage director when I first interviewed him, gets a LOT of movie into this film’s 93 minutes.

“Immortal Life” deals with the arcane science of the story in a whirl of montages, and a black and white prologue that covers what those “HELA” (for “HEnrietta LAcks”) cells were used for in the decades after they were removed from Lacks, dying of cervical cancer and treated at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

This film, like the Rebecca Skloot book it is based on, is about the consequences of Lacks’ death at 31, of the removal of those cells, the fact that this happened at the tail end of some of the most egregious medical “experimenting” on African Americans and that corner of American culture’s long mistrust of the American medical establishment in general and more locally, Johns Hopkins U. Hospital in particular.

The narrative here is about Lacks’ children, the physical, psychological and financial costs her early death brought to her sons and one surviving daughter, Deborah, who has no memories of her mother and wears that trauma in every mercurial, manic-depressive reaction she has to a reporter who wants to tell her mother’s story.

Oprah Winfrey gives her finest film performance in this role, a woman consumed by past acts beyond her control, passionate to learn about her mother and prone to psychotic rages about the injustices done to Henrietta, her family and Deborah in particular. Deborah, above all else, wants her mother’s story told, but she’s furiously paranoid of any writer who might take on the job, who might be backing that writer and where this story’s profits would go.

Others had written about “the immortal cells,” which were a singular success as a line that proved durable enough to replicate on and on in the lab after Lacks’ death, and how they were instrumental in finding cures for polio, tuberculosis and HPV, and treatments for everything from cancer to AIDS to COVID.

What science-and-medical freelance reporter Rebecca Skloot wanted to do was delve into Henrietta’s barely sketched-in story. She’d get that from scholarly articles and medical history and records, and from Henrietta’s surviving family. That would prove to be its own Herculean task, thanks to family history, poor record keeping and mistrust about what happened to their mother, and how decades of exploitation of her made others rich and the family still working poor.

Skloot is played with that pasted-on “patient” smile every reporter (and a lot of women in general ) wear when dealing with difficult people — here, downright hostile interview subjects — by Rose Byrne.

Wolfe and co-writers Peter Landesman and Alexander Woo build their film around Deborah Lacks and Skloot, their difficult relationship and struggle over how to tell this tale and what to include in it, and the emotionally wrenching tug of war over one Black family’s tortured past and present.

The genius of the film’s casting is how well star-and-producer Winfrey and Byrne mesh, how Winfrey gets across Deborah’s limited education and grasp of how scientists “cloned” her mother, and how Byrne’s ever-smiling-through Deborah’s violent mood swings has its limits, but who comes to realize the actual hstory she’s dealing with even if this or that editor or publisher doesn’t.

Wolfe and his stars find humor in Deborah’s alarming mood swings, although the film can give you whiplash from the way the character and the tone changes with this piece of research or that breakthrough, which feels like a moment of welling pride and triumph. Then Deborah explodes again and all but shuts the project down.

Winfrey, Reg. E. Cathey, John Douglas Thompson and Rocky Carroll — as the surviving children — lean into their wary mistrust, their comical, crazy-like-a-fox “tests” and manipulations of this “white woman” who — whatever her motives — is able to get a lot further with the medical establishment than this “invisible,” dismissed Black family has ever been able to.

You go, girl. “You go on being white.”

The darkest laugh might be when Skloot gets a “cut out the family” direction from a publisher/editor, only to have the myopic fool die in a car accident, her excuse for ending their contract. Byrne finds just the right pitch for this scene, and every other one.

Courtney B. Vance vamps the hell out of a charlatan “lawyer” who tormented the family with promises he was incompetent to keep and venal, self-serving harassment when they figured him out.

“The Immortal Life” has poingnant and dynamic scenes from Cathey, and Leslie Uggams and John Beasley as relatives who remember Henrietta, glimpsed in flashbacks and played by Renée Elise Goldsberry.

Hers was an unremarkable and too-short life, which is why the focus of the film was wisely shifted to her family, the trauma of her loss and the traumas and abuses — medical and personal — that spun out of the tragedy of Henrietta’s death and the callousness of the system and the culture towards them.

The story’s unraveling takes place in Baltimore, but its heart-and-soul are in Clover, where the Roanoke-born Lacks grew up and where Skloot and Deborah uncover vanishing traces of Henrietta before they die out or fall down and blow away.

And let me add that the Branford Marsalis score to the film is a marvel — gorgeous, sometimes dischordant “free jazz” underlying the scenes in Baltimore, reflecting Deborah and her siblings’ fraut mental state and fury, folk blues setting the mood for the country world Henrietta grew up in, a farm in what was then labeled “The Heart of Tobaccoland.”

This terrific film’s less-than-stellar reception from critics and the Emmy Awards of that year may reflect a lot of things, not the least of which is a general “over it” response to Winfrey’s awards-bait project and the way she’s Big Footed her way through the culture past the point of some people’s tolerance. .

But released at a different time, under a different regime, this picture could have played in theaters and perhaps gotten its due.

I found it quite moving, almost wrenching at times, and it brought tears to many in the audience I saw it with, suggesting the communal experience of a cinema was its proper home all along.

And its heartening hearing locals in the county where she grew up talking up plans for a statue in her honor, to go along with the tombstone that finally marks her grave in Clover, over 70 years after Henrietta Lacks’ death.

A clever county grant writer might even be able to find some entity to undewrite restoration/rebuilding of the old Clover Rosenwald School Lacks attended in the Jim Crow South of her youth as a vistitor information center. Strike while the Henrietta iron is hot, kids.

But until then, Wolfe — he also directed the very fine “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” — Winfrey, Byrne and the cast have made a fine monument to a woman whose life might have been unremarkable, but whose death symbolized exploited and ill-used generations, and whose immortal cells quite literally changed the world.

Rating: TV-MA, disturbing images, profanity

Cast: Oprah Winfrey, Rose Byrne, Reg E. Cathey, Leslie Uggams, John Beasley, John Douglas Thompson, Rocky Carroll, Renée Elise Goldsberry and Courtney B. Vance.

Credits: Directed by George C. Wolfe, scripted by Alexander Woo and George C. Wolfe, based on the book by Rebecca Skloot, An HBO release.

Running time: 1:33